Contextualizing Timbuktu in the 1430s

In the 1430s, Timbuktu was a beacon of knowledge and wealth within the Mali Empire. Renowned for its significant role as an Islamic learning center, it attracted scholars and students from far and wide (Levtzion & Hopkins, 2000). You would witness a society where education was revered, and commerce thrived on the exchange of manuscripts alongside gold and salt. The diversity here stemmed from various factors including social class, education level, and involvement in trade networks.

Social Hierarchy and Class Distinctions

Navigating through Timbuktu’s societal layers would reveal a rigid social hierarchy that might seem unsettling by modern standards. Slavery was an entrenched part of life here; slaves worked in households or toiled in gold mines (Batran, 1973). In stark contrast to today’s ideals of equality, status was often fixed by birthright. Wealthy merchants flaunted their affluence while scholars were held in high esteem for their knowledge. This glimpse into the past underscores the advancements made towards social mobility and human rights since then (Levtzion & Hopkins, 2000).

Architecture and Urban Landscape

The architecture you’d encounter would be strikingly different from modern cities. Sudano-Sahelian structures like the Djingareyber Mosque stand tall with their distinctive adobe constructions (Clark, 1999). The use of organic materials like mud bricks is unfamiliar compared to contemporary steel or concrete buildings. Walking through labyrinthine streets laid out without an apparent plan might disorient someone used to orderly urban grids.

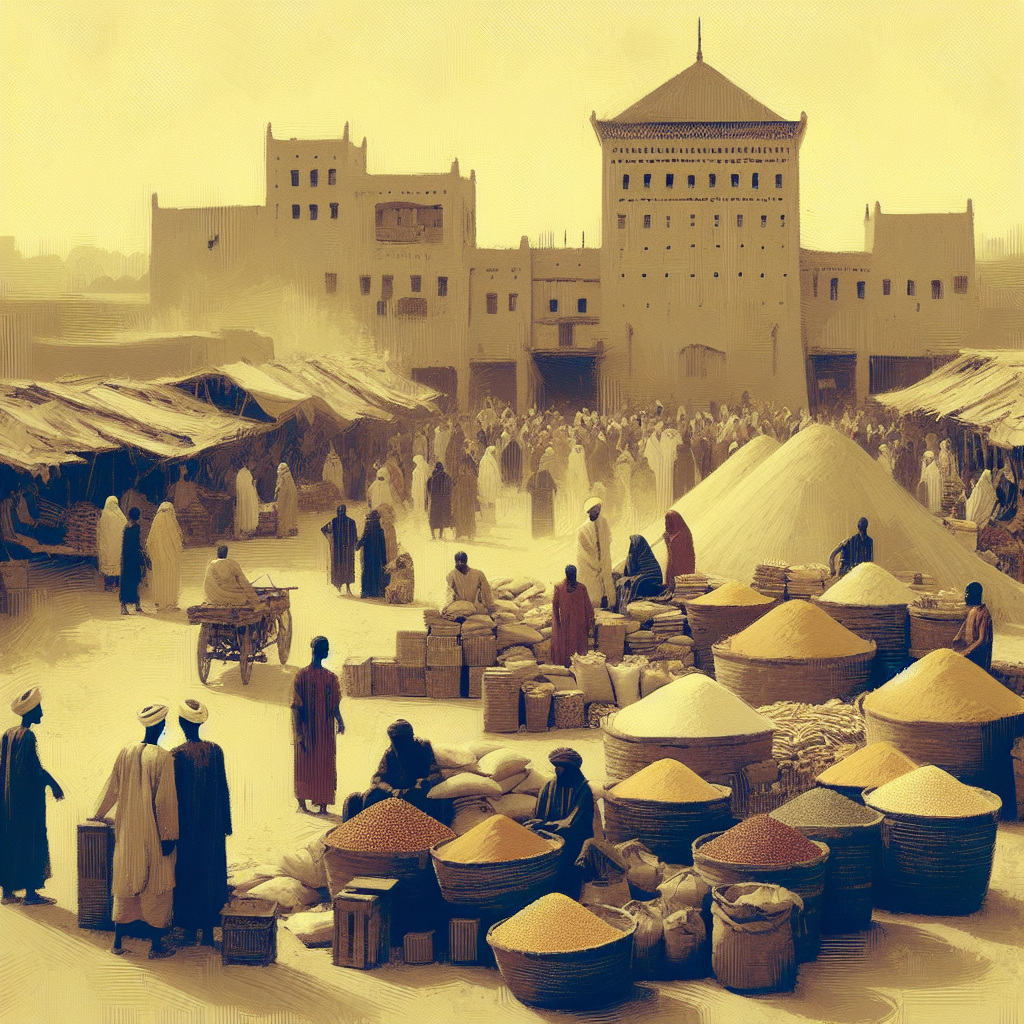

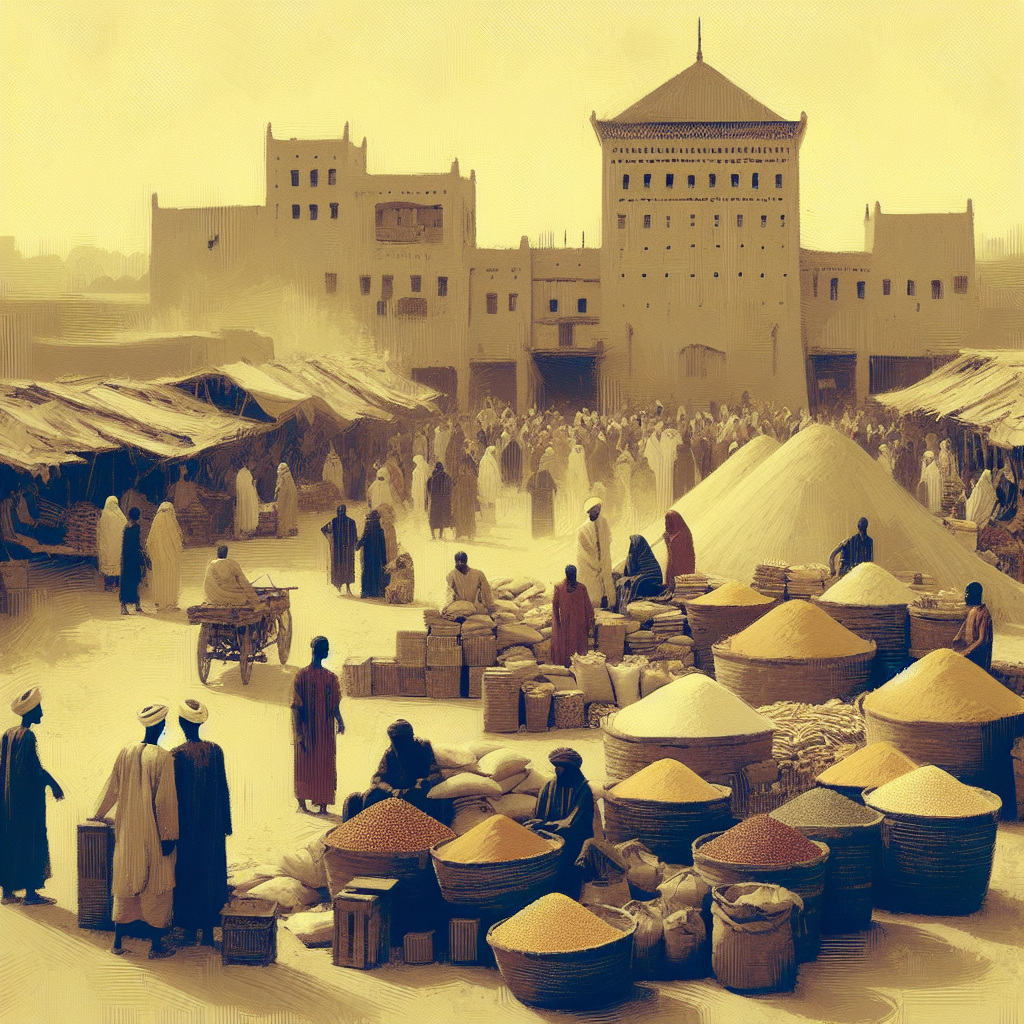

Economic Exchange and Ethics

The markets of Timbuktu would offer a unique perspective on economic exchange where gold dust served as currency (Bovill, 1995). Witnessing transactions involving slaves or ivory might provoke feelings of discomfort when viewed through today’s ethical lens. Such practices starkly contrast with modern commerce regulations that prohibit such goods’ trade due to moral considerations.

Access to Jobs and Food

In terms of employment opportunities, your status dictated your prospects much like how one’s resume does today (Hunwick, 2003). Scholars could aspire to prestigious positions at institutions like Sankore University while traders flourished thanks to trans-Saharan routes. Food security relied on trade as well as local agriculture—markets bustled with vendors selling grains like millet which were stored in granaries against lean times.

Health and Public Sanitation

Public health concerns echo across centuries; clean water from the Niger River was vital for sanitation just as clean water remains essential today (Levtzion, 1973). Ritual ablutions for prayer reinforced cleanliness practices similar to current hygiene standards. Healthcare involved traditional medicine for treating common ailments—a constant quest for wellness comparable to contemporary healthcare challenges.

Your journey through Timbuktu during the 1430s would span experiences ranging from relatable moments at marketplaces to confronting ethical dilemmas unheard-of in modern society. This voyage into history not only educates but also evokes deep reflections on how far humanity has progressed—and what has remained unchanged—at its core.

References:

- Batran, A.-A. (1973). “A Contribution to the Biography of Shaikh Muhammad Baghayogho al-Kunti al-Timbukti.”

- Bovill, E. W. (1995). “The Golden Trade of the Moors: West African Kingdoms in the Fourteenth Century.”

- Clark, A. (1998). “Reflections on the Sankore Madrasah,” Sudanic Africa.

- Hunwick, J. (2003). “Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Sadi’s Tarikh al-Sudan down to 1613 and other contemporary documents.”

- Levtzion & Hopkins (2000). “Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West African History.”

- Levtzion N., (1973) “Ancient Ghana and Mali.”